#kidlitwomen, is a month of essays and posts about gender inequities and other disparities in children’s literature. Join the conversation at KidlitWomen on Facebook and by searching #KidlitWomen on Twitter.

When my editor sent me the cover concept for my upcoming novel, ANYTHING BUT OKAY, I liked it – a lot. Nonetheless, there was something that concerned me, and I wrote back posing the question of cover gendering.

My last three YA novels all have a technology element. As far as protagonists:

BACKLASH is told from four points of view, three female, one male.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT is from the point of view of a bright female who does probability trees to figure out if the guy she likes will invite her to the dance, and if she should accept if another guy asks her first.

ANYTHING BUT OKAY is told primarily from a female point of view, but with part of the story told in diary entries from the main character's older brother, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan who is struggling with PTSD.

Here are the covers:

In comparison, I looked at the covers of some well-known male YA authors who also published books with a female protagonist, including several from my publisher.

Here are some examples:

When I look at these, I can't help but wonder if this is truly a branding and marketing issue or it’s gendering issue. Even the covers by male authors that do feature a girl on the cover are in more gender neutral color palettes. Not a hint of pink to be found. Why does this matter? Because despite the admonition that we "shouldn't judge a book by its cover", we all know that's what happens.

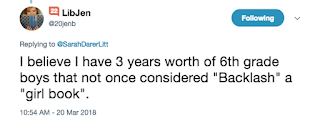

I’m by no means the first one who has raised this. Back in 2013, Maureen Johnson tweeted to her followers: I do wish I had a dime for every email I get that says, “Please put a non-girly cover on your book so I can read it. - signed, A Guy”. She then had the genius idea for a Coverflip.

The results were illuminating, as you can see here.

Jennifer Lynn Barnes wrote a fascinating post the causality of a book's success and gender.

There are important reasons why we need to examine this more closely, particularly now that #Metoo has started past-due conversations about harassment. Covers create a perception of the book, and that translates to school visits - an important source of income for authors, and a source of book sales, which then translate to other forms of recognition - the cascading model, as Jennifer put it.

At a school visit not long after my novel IN CASE YOU MISSED IT came out, the media specialist told me that she almost had me only speak to the girls, because I write “girl books”.

I don’t think of myself as a writer of “girl books.” I do my best to create intelligent, thoughtful female characters with a full range of emotions – just as I do with my male characters. Then I put them in situations where they have to make choices, choices which are difficult because the answers aren't clearly spelled out in black and white. The grey areas of the human experience fascinate me, because it's those choices, as Albus Dumbledore observed: "that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities."

As far as I’m concerned, I write books for thinking human beings of any gender. Not only that, my school visit presentations cover completely non-gendered topics like research, the important of writing well no matter what you do in life, inspiration, creativity, and persistence. There are even butt jokes and corpses.

I asked the media specialist what message she was sending to both boys and girls if the girls were required to listen to male authors, but boys weren’t required to listen to female authors.

Her reply: “I never thought of that.”

It's just not good enough. We all need to think a harder about that, because the messages we’re sending boys are ones that will stick with them when they are men in college and the workplace. If we’re not part of the solution, we’re part of the problem. Boys shouldn't grow up with the message that women's voices are unimportant and can be ignored. Shannon Hale has been powerfully outspoken on this.

When I asked other female kidlit authors for their thoughts, I heard a depressingly familiar story.

Here's Melanie Crowder:

I did a middle school assembly-style visit with a group of debut authors in 2013. We were brand new, bright eyed and enthusiastic, but the school nearly cancelled at the last minute. When I approached the principal before the visit he said something along the lines of: "Oh, we almost cancelled because you're all women and we didn't think the boys would get anything out of it."

A woman author who wished to remain anonymous told me: “I was meeting with a bookseller who is influential in selecting our city-wide read. She was flipping though my books, looking for one that had broad enough appeal for the program--and she made it very clear that by broad appeal, she meant one with a boy protagonist.”

Christina Soontornvat spoke of a problem that is all too familiar:

"I have gotten so many comments of "Do you think my son would read this?" or "Oh, we have some girls in our class who would love that". Too many comments to keep track of! But when kids are allowed to choose, I find that boys tend to like them in the same proportion as girls do. "

At least she gets asked if the adult's son would read it. I get people just telling me: "Oh, it looks great, but I only have sons/grandsons/nephews." They take one look at my covers and ASSUME that the book wouldn't be of interest - and I can't help but wonder if it would be the same story if my covers were more like the male author ones above.

What's particularly depressing is how young kids are when they get this message from parents and gatekeepers. Here's picture book author and journalist Dashka Slater: "I have watched parents literally take copies of my book Dangerously Ever After out of their sons' hands because it's about a princess."

We all know how subversive it would be for a young boy to read about a princess. Heck, he might grow up to respect and understand women better!

Here's an unutterably depressing story from Newbery award-winning author Linda Sue Park.

One of my books, KEEPING SCORE, is a baseball book with a girl protagonist. Uphill work getting boys to read it, sigh. When the paperback jacket was dummied, the publisher showed it to me. It had even MORE 'girl' markers (more pink, very domestic scene). I told them about the difficulty of getting boys to even open it. They switched to a cover with a DOG. Boom! Boys read it now. It's such a quandary: Is it better to have the dog on the cover so boys will at least open it, and read about a girl character? Or leave the girl on the cover while we work on dismantling the patriarchy--which means countless boys WON'T read it, at least for now.... OY."

What does that say about the messages we adults send young men and boys, that they will pick up a book with a dog on the cover over one with a girl - even if it's about baseball?

I know that boys DO read my books, and again, I can't help wondering how many more might if my covers were more gender neutral.

Here's Jen Brooks, a media specialist in Findlay, OH:

Sayantani Das Gupta wrote:

On the flip side my new female protagonist mg book with a brown girl on the cover front and center is actually getting really good reception so far from boys and girls and teachers seem to be pushing it toward both - is it because it’s a funny fantasy and not realistic fic? I don’t know .

It's an interesting question. I wonder if it's because it's humorous fantasy or that one can get away with more when it's a drawing of a girl than photograph? Or if it's because middle grade rather than YA?

Holly Westlund was working as a bookseller when Marie Rutkowski's WINNER'S CURSE trilogy first came out.

I think THE WINNER'S CURSE trilogy is an excellent example of series that should realistically appeal equally to both genders and was marketed to girls only (see covers), despite the dual protagonists.

Maureen Johnson made the papers when she highlighted the gendered covers issue in 2013. Sadly, five years later, it doesn't seem like much has changed.